I’ve been thinking a lot about what it takes to survive, especially amid this moment when life feels very precarious.

A few days ago, a colleague of mine sent me this article, which profiles a community of 14,000 Vietnamese people who call East New Orleans home. This small but resilient group has survived every form of disaster including:

- The catastrophic Vietnam War

- Forced migration as a result of said catastrophic war

- The innumerable challenges – poverty, racism, food insecurity, intergenerational trauma – that come with assimilating to the United States

- The BP Oil Spill, which ravished Vietnamese fishing communities along the Gulf Coast

- Hurricane Katrina, which sent this community into seeking refuge again

- And now a global pandemic that could economically destabilize the community and threaten an elderly population that has survived everything listed above

I write out all of these barriers not to solicit dread, but to revel in awe. Despite the dire circumstances impacting this multi-generational Vietnamese neighborhood, I have little doubt that the community will continue to survive. This East New Orleans neighborhood, known colloquially as “Versailles”, has been the subject of several documentaries and research papers because it is the embodiment of “community resilience” – the ability of a collective to organize and use physical, human, and political resources to recover quickly from an adverse situation.

Historically, Vietnamese people have survived and endured to an astonishing and dangerous degree. That isn’t to say that all Vietnamese people are doing well – I’m not into that model minority bullshit. However, Vietnamese people are a part of a culture and a nation-state that has withstood a thousand years of Chinese tributary rule and has overthrown French, Japanese, and American occupiers – not to mention our ability to persist through incredible heat, high humidity, awful traffic, warm beer, obnoxious uncles, and terrible karaoke.

Vietnamese people are like that big ass spider that freaks you the fuck out when you step into shower – the one that makes you think “Oh shit! I’m naked and in a tub with a spider!” We’re that spider that makes you reach for the shower head, drown the shit out of it, and feel momentary relief watching its balled-up body swirl around the drain. We’re that spider that slowly unfurls right as you expect us to disappear – that’ll survive even as you pound us with the shampoo bottle and douse us with soap. We’re that spider that will causes you to scream, “Why won’t this thing fucking die?” and then conclude that it may just be better to give that spider some space, walk out of the bathroom, and shower at another time.

That spider is probably Vietnamese. Perhaps my cousin.

But how? What does community resilience, self-sufficiency, and survival look like in practice? When I think of the absolute fortitude that comes with living, I think a lot about my own mother. Ali Wong jokes that Asian women are bad drivers because “we’re trying to die” – a truism for my own mother who is an abysmal driver and who has literally told me that “dying is really hard to do”. That’s a bold statement coming from someone who has had many opportunities – too many opportunities – to test that hypothesis.

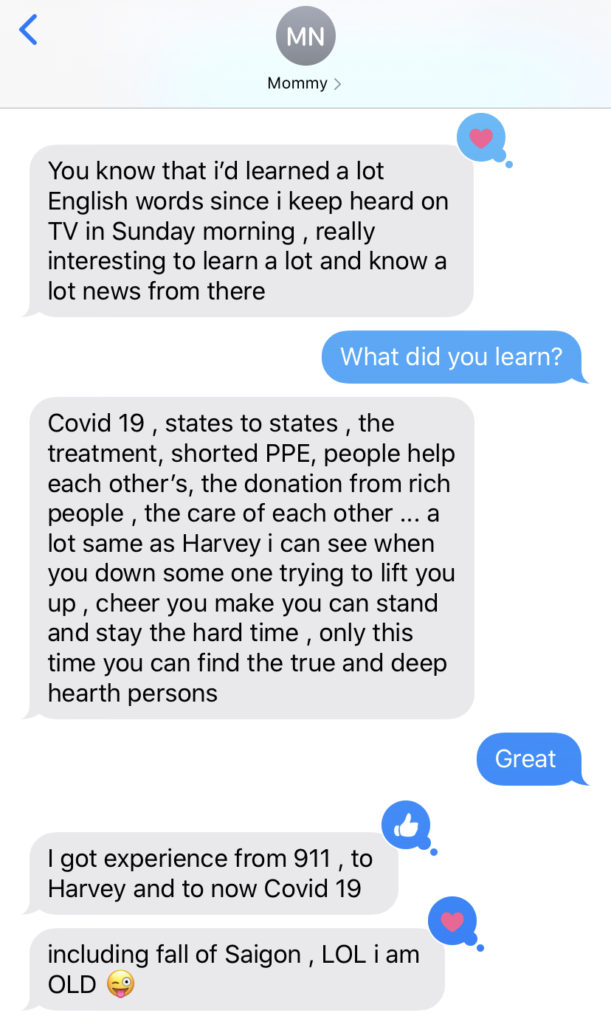

If I could distill her formula for withstanding life into a few ingredients, the first would be her general life disposition. She approaches life with a laidback “whatever will be will be” attitude and couples it with a strong sense of curiosity and wonder. Successes and struggles are pieces of data that drive and iterate a life-long learning experience. Life is too busy and hard for over-analysis. While most people recoil while watching the news, here’s how my mother is taking it in:

Second, my mother is able to harbor a relaxed attitude because she has learned to be incredibly resourceful. One could also say that she is just completely extra – an over-planner, over-preparer, over-everything type of woman. She’s her own presidential Defense Production Act, her own stockpile, her own reserve. In fact, here’s a comprehensive list of her responses to COVID-19:

- Stockpiling 2 freezers of frozen food – one freezer specifically dedicated to individually wrapped (why?) Costco bread

- Stockpiling at least 2 dozen containers of vitamins, including at least 3 bottles of Vitamin D (why?)

- Teaching herself how to make her own antibacterial soap l out of essential oil, rubbing alcohol, and aloe vera – and sending her own daughter out in the middle of a pandemic to acquire all of these materials

- Putting her homemade antibacterial liquids into travel sized Tresemme hair gel containers

- Somehow accumulating and having the foresight to save several travel-sized Tressume hair gel containers

- Hand sewing her own masks

- Hand sewing her own 2-sided reversible masks

- Hand sewing her own 2-sided reversible masks with adjustable ear bands

- Borrowing a sewing machine to produce more than a dozen 2-sided reversible, adjustable ear band masks in assorted colors and patterns including bunny rabbits and pandas!

- Sending a care package of 2-sided reversible, adjustable ear band masks in assorted colors and patterns to her daughters

Let’s talk about over-resourcefulness as a response to unresolved trauma next time, eh?

For now, I’ve been thinking a lot about what it means to survive – emotionally, physically, socially. And although times have been incredibly trying, I am trying to lean on the incredible community and familial examples of surviving and thriving in my life. I hope you are too.